Suppose you’re planning to launch a new soda brand, and need to think of an incredible brand name. You know what soda drinkers like, and you consider yourself pretty creative—why not just come up with the name yourself? What could go wrong?

You might wind up with a name like Nokia’s “Lumia,” which means “prostitute” in Spanish. Or something hard to spell and pronounce in some parts of the world, such as “Hoegaarden?” These stumbles could be embarrassing and, possibly, expensive. However, the worst slip-up you could make—the “killer mistake” to avoid—would be accidentally picking a name that a similar brand is already using.

Imagine you’d (somehow) never heard of Coca-Cola, and so you decided to use that name for your new drink. What would happen? Lawyers from The Coca-Cola Company would probably send you a letter nicely suggesting you “step off” their trademarked brand name.

Granted: everyone’s heard of Coca-Cola (and who’d want to name their soda brand after cocaine, anyway?), but this illustrative example makes an important point about the hazards of naming. Now, let’s look at some real-world examples of the perils of trademark (un)availability in naming. Each of these cases is different, and some may not add up to much from a legal standpoint. But together, these cases show that brand naming isn’t purely a creative exercise—it’s also about strategy and rigor.

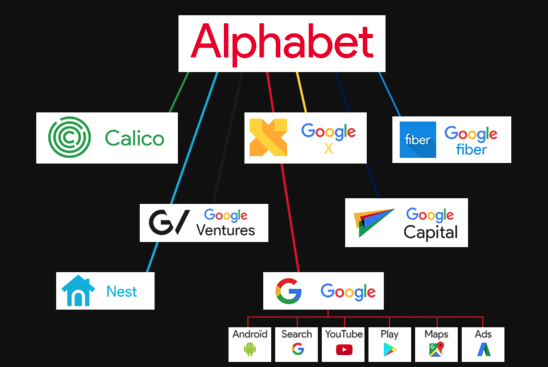

Google Becomes Alphabet; BMW Has A Trademark On “Alphabet”

When Google restructured, and the parent company became Alphabet, The New York Times pointed out several other companies using the same name. One of them, BMW, owns alphabet.com and says it “does not want to sell.” But the article goes on to suggest Google may not face legal troubles as a result of the name: “Just because one company uses a name does not mean another company cannot use it.” True, trademarks are typically limited to a particular class of goods and services. Think Dove soap and Dove Chocolate.

Alphabet (née Google) and BMW do have some overlapping businesses (Waymo’s self-driving vehicles, for example), but that doesn’t necessarily mean Google will be in legal hot water. And as far as the domain goes, Google snagged a witty URL for Alphabet: abc.xyz.

JDate And JSwipe

JSwipe, the “number one Jewish dating app,” asked supporters to help cover their legal fees so they could defend themselves against JDate, another online dating service for single Jewish people. JDate tried to claim “intellectual property over the letter ‘J’ within the Jewish dating scene.”

JSwipe, the smaller company, is calling foul, saying JDate wants to bully them into selling their company. After all, a number of other apps for Jewish users begin with “J.” But Michael Egan, the CEO of JDate’s parent company, argues “swipe” is synonymous with “dating.” “Before they even built a brand,” Egan says, “it would have been very easy for them to take a different name; it’s not like they had built or spent a lot of money to build that name.”

Whether or not JDate’s case is legitimate, it sounds like JSwipe could’ve avoided all this trouble by simply choosing a different name.

From Poachable To Anthology

Tom Leung, co-founder and CEO of Poachable, wrote, “unfortunately, we hit some roadblocks about whether the name [Poachable] could be registered as a trademark.” In a blog post, he explained why the career matchmaking company was renaming itself to “Anthology.” Leung told more of the story in an Inc. article: “We were on our way to becoming a household name; that is, until we heard from the United States Patent & Trademark Office…To make a long story short, the USPTO refused our application for ‘Poachable,’ citing alleged similarity to two other trademark holders, ‘Poached’ and ‘Poachee.'” After attempts to negotiate with Poached and Poachee, however, Leung and his company found themselves “facing the daunting prospect of having to start from scratch. Thus began a long, intensive journey to rename the company.”

It’s is a worst-case scenario for a brand name: After investing in the brand and name for over a year, the company has to start over, find a new name, and explain the change. The costs of that change include legal fees, customer confusion, and launching an entirely new brand.

Three Lessons For Naming

What can we learn from the stories above? At least three lessons come to mind:

Case A Wide Net

Every year, thousands of trademark applications are filed with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. You’ve probably heard stories of entrepreneurs coming up with brand names using Scrabble tiles or flipping through the pages of a dictionary, but legal constraints alone make this a risky proposition. Even if name ideas are legally available, they may cause linguistic or cultural disasters when companies expand into new markets (e.g., Lumia).

To find legally available, linguistically viable name ideas, namers (and branding agencies) come up with hundreds of name ideas. Quantity leads to quality. By keeping options open and narrowing the list down to a few, strong options, companies have backups in case their top choices “fall out” during legal or linguistic screening.

Keep An Open Mind

When Larry Page introduced Alphabet to the world, he wrote, “Don’t worry, we’re still getting used to the name too!” And Tom Leung of Anthology gave the following advice: “Don’t overreact if people don’t swoon” when you share your new brand name. Every day, we encounter “strange” brand names—Casper, Chrome, Virgin, Apple—without batting an eye. Try to get past that instinctive, skeptical reaction to a new name. Names that sound a bit funny at first may still work beautifully in the long run.

Rather than seeking out the weaknesses in new ideas, imagine what they could become with all the right support. After all, names rarely stand alone—they typically come with a logo, copywriting, and more. With time, they’ll take on new meaning. If we can drink a Starbucks, Google the answer to a question, and blow our nose into a Kleenex, surely our brains are more than flexible enough to adapt to the likes of “Alphabet” and “Anthology.”

Get A Lawyer (A Trademark Attorney)

The three stories above illuminate one final lesson: get advice from an experienced trademark attorney before it’s too late. Just because you secured [name].com doesn’t mean it’s legally available. And no, slightly changing the spelling of a word probably won’t get you around the problem, either.

Unless you’re an expert, be careful trusting your own opinion of whether a company or product is “similar enough” to yours to be cause for concern. You’ll be biased toward downplaying the risk, but try to put yourself in the other company’s position—how would you feel if another brand launched with a similar name? Would it confuse your customers? By answering these questions based on experience and expertise, a trademark attorney can help you accurately assess the legal risk of using a name.

Next time you’re naming something, keep these lessons in mind. Hopefully, you’re lucky enough to find a name you love that’s available and “safe” to use. Expect the best, but plan for the worst: Stick to a rigorous naming process and pay attention to legal availability. Find a name that’s memorable, unique, and creative—and that you won’t have to change after a year.

(Editor’s Note: This article was previously published by TechCrunch.)

Rob Meyerson is a San Francisco-based brand strategist and namer with experience ranging from startups to the Fortune 100. Twitter: @RobMeyerson